[ad_1]

RIO DE JANEIRO: Each New Year’s Eve, more than 2 million revellers – twice as many as typically fill Times Square – dress in white and pack Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro to watch a 15-minute midnight fireworks extravaganza. The one-night hedonistic release is one of the world’s largest New Year’s celebrations and leaves Copacabana’s famed 2.4 miles of sand strewed with trash.

But it began as something far more spiritual. In the 1950s, followers of an Afro-Brazilian religion, Umbanda, began congregating on Copacabana on New Year’s Eve to make offerings to their goddess of the sea, Iemanja, and ask for good fortune in the year ahead. It quickly became one of the holiest moments of the year for followers of a cluster of Afro-Brazilian religions that have roots in slavery, worship an array of deities and have long faced prejudice in Brazil. Then, in 1987, a hotel along the Copacabana strip started a December 31 fireworks show. It was a huge hit that began attracting large numbers. “Obviously, this was great for the hotel industry, for tourism,” said Ivanir Dos Santos, a professor of comparative history.

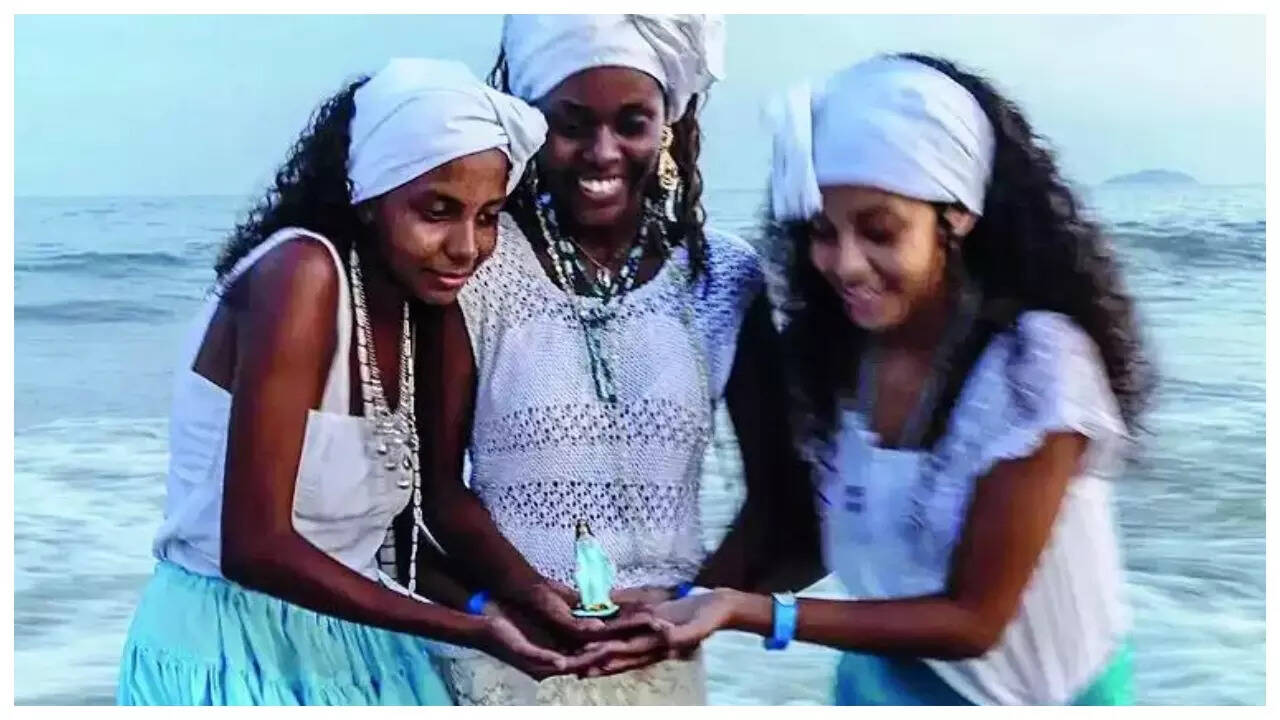

A new New Year’s tradition was born, and the revellers adopted some old Umbanda traditions, including throwing flowers into the sea, jumping seven waves and, especially, wearing white, a symbol of peace in the religion. But the huge party, Dos Santos said, “also then pushed the worshippers off the beach.” Not entirely. Dos Santos was standing on Copacabana Beach, dressed in white, with the chants of Umbanda worshippers behind him. Yet this was December 29, the date when devotees of the Afro-Brazilian religions now descend on Copacabana Beach to make their annual offerings to Iemanja. Alongside beachgoers in bikinis and vendors selling beer and barbecued cheese, hundreds of worshippers were trying to make contact with one of their most important gods. Devotees believe that Iemenja, who is often depicted with flowing hair and a billowing blue-and-white dress, is the queen of the sea.

Many gathered under a tent for traditional dances and songs around an altar of small wooden ships, loaded with flowers and fruit, that would be sent into the sea. Outside, they dug shallow altars in the sand, leaving candles, flowers, fruit and liquor.”This is a tradition passed from generation to generation,” said Bruna Ribeiro de Souza, 39, a schoolteacher. Alexander Pereira Vitoriano, a cook, carried one of the largest boats and waded into the waves first. As he let the boat go, a wave capsized it, a sign to the followers that Iemenja had taken the offering. “She comes to take everything bad to the depths of the sacred sea, all the evil, the sickness, the envy,” he said. “It’s a clean start to the new year.”

But it began as something far more spiritual. In the 1950s, followers of an Afro-Brazilian religion, Umbanda, began congregating on Copacabana on New Year’s Eve to make offerings to their goddess of the sea, Iemanja, and ask for good fortune in the year ahead. It quickly became one of the holiest moments of the year for followers of a cluster of Afro-Brazilian religions that have roots in slavery, worship an array of deities and have long faced prejudice in Brazil. Then, in 1987, a hotel along the Copacabana strip started a December 31 fireworks show. It was a huge hit that began attracting large numbers. “Obviously, this was great for the hotel industry, for tourism,” said Ivanir Dos Santos, a professor of comparative history.

A new New Year’s tradition was born, and the revellers adopted some old Umbanda traditions, including throwing flowers into the sea, jumping seven waves and, especially, wearing white, a symbol of peace in the religion. But the huge party, Dos Santos said, “also then pushed the worshippers off the beach.” Not entirely. Dos Santos was standing on Copacabana Beach, dressed in white, with the chants of Umbanda worshippers behind him. Yet this was December 29, the date when devotees of the Afro-Brazilian religions now descend on Copacabana Beach to make their annual offerings to Iemanja. Alongside beachgoers in bikinis and vendors selling beer and barbecued cheese, hundreds of worshippers were trying to make contact with one of their most important gods. Devotees believe that Iemenja, who is often depicted with flowing hair and a billowing blue-and-white dress, is the queen of the sea.

Many gathered under a tent for traditional dances and songs around an altar of small wooden ships, loaded with flowers and fruit, that would be sent into the sea. Outside, they dug shallow altars in the sand, leaving candles, flowers, fruit and liquor.”This is a tradition passed from generation to generation,” said Bruna Ribeiro de Souza, 39, a schoolteacher. Alexander Pereira Vitoriano, a cook, carried one of the largest boats and waded into the waves first. As he let the boat go, a wave capsized it, a sign to the followers that Iemenja had taken the offering. “She comes to take everything bad to the depths of the sacred sea, all the evil, the sickness, the envy,” he said. “It’s a clean start to the new year.”

[ad_2]

Source link